Reusing and Publishing Data

Reusing data

Research datasets

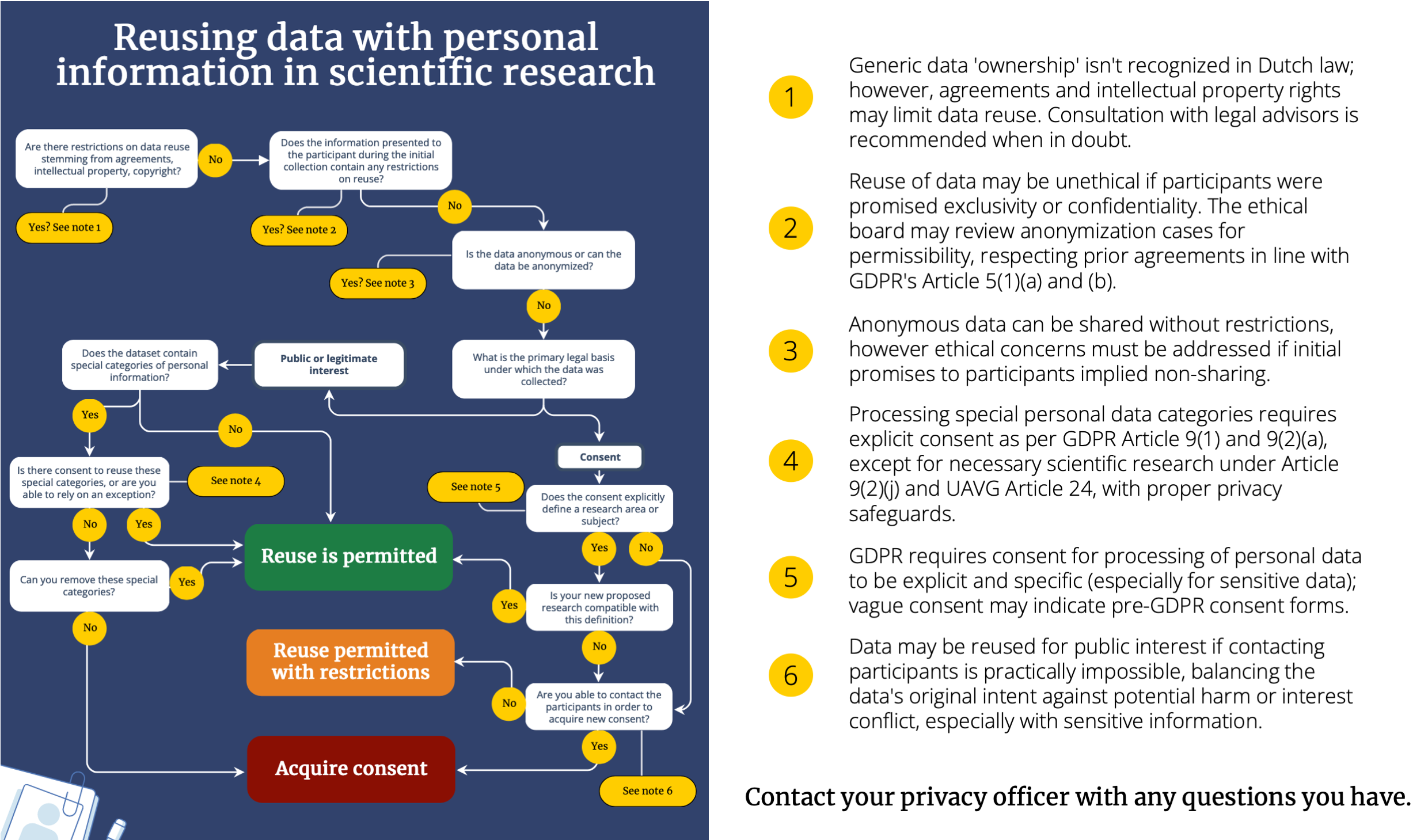

Sometimes you will not collect a new dataset from participants, but rather use an existing scientific dataset. If this dataset contains personal data, reuse is not automatically permitted. Below an extensive flow chart that aims to provide some assistance in establishing whether reuse of scientific data is permitted. It does not matter whether you are using data collected yourself, or whether it has been collected by a colleague at another institute. Of key importance for FSBS researchers is what participants were initially told their personal data would be used for, and whether reuse is compatible with those parameters. For example, if your participants were initially told their data would not be shared with anyone, even sharing their data anonymously may be unethical (relates to principles of ‘fairness and transparency‘, GDPR, article 5(1)(a)).

Decision tree for the reuse of scientific information. A more comprehensive version can be downloaded here.

Data not initially collected for scientific research purposes

You can also use personal data that was initially collected for other purposes than scientific research (when the initial legal basis was either legitimate interest, a contract or vital interests), such as grades in Osiris, attendance records, or data from other organizations. In such instances, scientific reuse is considered compatible with the original processing purpose, provided that appropriate safeguards are implemented (GDPR, Recital 50). These safeguards include adhering to data minimization principles, employing pseudonymization, and anonymizing data where feasible (GDPR, article 89(1)). In cases where the original legal basis for processing was consent, the restrictions of that consent (which should contain specific parameters for data use) remain valid (source). When the dataset contains special categories of personal data, processing requires additional consent. The exception is when processing is serving a public interest, but asking for consent proves impossible or requires an unreasonable effort, and processing the data will not cause disproportionate harm to the participants.

Informing participants

People have the right to be informed about any new processing of their data. However, there is an exception for scientific research: if providing this information is impossible or requires unreasonable effort, the information obligation can be waived. In such cases, technical and organizational measures must still be taken to protect the rights and freedoms of the individuals and ensure minimal data processing.

Social media scraping

If you are planning to reuse data from social media, follow these steps to ensure your research complies with legal and ethical standards:

- Verify whether the data includes personal information.

- When your research is done with public interest as a legal basis, you are not required to obtain consent for the processing of personal data. When the scraped data contains special categories of personal data, you need to obtain consent. Otherwise, you will need to justify why obtaining additional consent from data subjects is impractical or would require unreasonable effort.

- Review and adhere to the terms and conditions of the social media platforms you plan to scrape.

- Be transparent about your data collection and usage processes. Provide public disclosures on your methods and intentions.

- Use only the data necessary for your research, implement safeguards like anonymization to protect individuals’ privacy during processing, and avoid publishing results that could (indirectly) identify individuals. Already make a selection of the variables you are interested in before scraping the data, so that you will not collect more information than you may need.

Publishing data

You may want to make your dataset publicly available, either accompanying an article or on an open repository. However, especially when dealing with personal data, this is not always permitted. Questions you will need to ask yourself:

- Are there restrictions on data reuse stemming from agreements, intellectual property, copyright? While the concept of ‘data ownership’ does not exist under Dutch law, there may be restrictions stemming from signed agreements with partners, or things like intellectual property or copyright that prevent the publishing of the dataset. Read more about this at auteursrechten.nl.

- Does the information presented to the participant during the initial collection contain any restrictions on sharing? If participants were initially told data would not be shared with other researchers, kept confidential or would not be used for any other purpose than the current research, then sharing is not permitted. The Ethics Review Board may decide in on whether publication after anonymization is still permissible in that case.

- If the data contains personal identifiable information, anonymize the data. Remember, anonymization may not always be possible. In addition, there may be ethical restrictions in reusing the anonymous data when participants were explicitly told nothing would be shared during the initial data collection.

If the dataset is fully anonymous, publishing it as an open dataset is permitted (barring any restrictions stemming from points 1 and 2). When in doubt, contact the privacy officer.

If the dataset does contain personally identifiable information, making it publicly available is problematic. Because, publishing personal information, even with consent, can conflict with the GDPR (articles 5(1)(c) and 4(1)(c)), which provides that personal data must be “adequate, relevant and limited to what is necessary in relation to the purposes for which they are processed”. Furthermore, under article 6(1)(a) of the GDPR, consent must be given for one or more specific purposes. Can the publication of a dataset be seen as ‘specific enough’? Publishing data containing personal information can also make it difficult (or impossible) for participants to exercise their ‘right to be forgotten’ (articles 17 & 19), as further reuse may be the intended goal of the publication. Finally, participants are allowed to withdraw their consent. Participants need to be made fully aware of these issues. For some types of data publishing them may be a trivial decision, but for more sensitive categories or complex types of data require a serious weighing of pros and cons.

While on the one hand, individuals have the autonomy to determine how much of their data they wish to disclose, and to accept the risk associated with the potential loss of control over data once it becomes publicly available, recognizing the challenges in effectively removing such data once released. On the other hand, researchers should perhaps protect participants from themselves and be cautious with sharing their data. Therefore, it’s advisable to consult with the ethics committee to determine if disclosure is truly permissible. Furthermore, when personally identifiable information is published to the public domain, those reusing the data will also need their own legal ground under the GDPR to do so.

In conclusion, it remains advisable to aim for fully anonymous datasets when publishing data. When this is not possible, publish with restricted access to better safeguard the rights of the participants.